The March on the Capitol rhymes with Mussolini's 1922 March on Rome

Why scholars call Trump a fascist now.

In the week pro-Trump extremists stormed the Capitol, I read award-winning Italian novelist and physicist Paolo Giordano’s warning that we shouldn’t see 2021 as a fresh start.

The vaccines’ arrival will not be as liberating as we think, the best-selling author of The Solitude of Prime Numbers said in Italian newspaper Corriere della Sera. When this virus goes away, other variations or pandemics will come. In our hyper-connected and populated world, we have to learn to live with them.

Instead of focusing on a new era, we’d better learn from the mistakes we’ve made and prepare for future health crises.

Giordano’s country had seen a violent insurrection to democracy when Benito Mussolini’s henchmen marched to Rome almost a hundred years ago.

This week’s events show that the same is true for that long thought-to-be-gone threat to democracy: fascism.

Giordano’s country had seen a violent insurrection to democracy when Benito Mussolini’s henchmen marched to Rome almost a hundred years ago.

On October 24, 1922, the then Italian Member of Parliament said in front of 60,000 militants at a rally in Naples: “Our program is simple: we want to rule Italy.” The following day, Mussolini appointed Emilio De Bono, Italo Balbo, Michele Bianchi, and Cesare Maria de Vecchi to lead a march.

Mussolini did not participate in the march himself but returned to his headquarters in Milan. A few days later, thousands of fascist protesters and paramilitaries entered Rome. Prime Minister Luigi Facta aspired to declare a state of siege, but King Victor Emmanuel III overruled it and appointed Mussolini prime minister on October 29.

The event in Washington D.C. echoes earlier times when political leaders let the violence unfold at a safe distance.

“History never repeats itself exactly, but it often rhymes,” as Mark Twain, without any substantive evidence, is reputed to have said. The March on the Capitol rhymes with the March on Rome.

We saw an elected political leader inciting violence. Then we saw protesters, some in bulletproof vests, helmets on their heads, even carrying weapons, storming the United States of America’s federal parliament.

“We want to be so respectful of everybody, including bad people,” President Trump said in front of thousands of protesters in Washington D.C. But “we’re going to have to fight much harder. [...] We fight like Hell, and if you don’t fight like Hell, you’re not going to have a country anymore. [...] We will walk down Pennsylvania Avenue and go to the Capitol.”

At the end of his speech, Trump returned to the White House. The event echoes earlier times when political leaders let the violence unfold at a safe distance.

In Poland and Hungary, the executive power has sidelined the judiciary, attacked the free press and universities, and humbled the legislature.

Recent authoritarian leaders in Poland and Hungary have sidelined the judiciary, attacked the free press and universities, and humbled the legislature. Matthew Goodwin and Roger Eatwell, authors of the best-selling National Populism: The Revolt Against Liberal Democracy, never went as far as to call these new regimes ‘fascist’. Instead, they called them ‘illiberalists’ or ‘national-populists.’

Likewise, Eatwell and Goodwin have argued for years that Trump was closer to illiberal populism than fascism. Trump was not overtly anti-democratic, and he was shunning violence. Illiberal populists, like Hungarian prime minister Viktor Orbán, relapse into ‘a gradual weathering of democratic norms’. But fascists go further by tearing down the entire democratic system through revolutionary and violent uprisings.

After the attack on the Capitol, Goodwin thinks Trump is closer to the fascists than populists. He didn’t destroy the entire democratic system (yet), but he definitely set the stage for it, Goodwin wrote on Twitter.

According to Yale-professor Timothy Snyder, Trump declared journalists the ‘enemies of the people’ and tried to destroy the concept of truth—something fascists managed to do a century ago. In books such as On Tyranny and The Road to Unfreedom, Snyder did not argue that Mussolini’s fascism reproduces itself today. Instead, he named the current extremist politics as ‘not-even fascism.’ Mussolini wanted people demonstrating out in the streets; the not-even fascists want people to stay at home in front of screens and on couches, alienated and indifferent to the erosion of democracy.

If you want to tell a big lie, which leads people to storm the building, then you have to expect that people are going to call this not just authoritarianism.

Timothy Snyder, like Matthew Goodwin, had to renew his analysis this week.

“If you want to tell a big lie, which leads people to storm the building, then you have to expect that people are going to call this not just authoritarianism but fascism,” Snyder said to NBC’s Mehdi Hasan on Wednesday. “I am afraid this is what it looks like.”

The history of fascism started before 1922 and continued after 1945. Our democracies are vulnerable. As during a pandemic, we shouldn’t lose our guard as soon as things get a little better. We have to continue arguing the cause for a free press, democratic elections, and the rule of law over and over again.

Tom Nuttall from The Economist asked whether the pandemic had a significant and lasting effect on European political parties’ standing.

…back to Europe

The coronavirus caused an economic crisis across the European Union. Unemployment is at 7.6%. That’s still better than in 2013 when unemployment rose above 11%, but the end of the second wave is not in sight. Economic distress proved to be a recipe for discontent and has ignited populist and fascist parties in the past. Tom Nuttall from The Economist asked whether the pandemic had a significant and lasting effect on European political parties’ standing. It seems some populist parties have swooped up seats other populist parties have lost. Some liberal, conservative, and social-democratic parties in government got more popular because of how they’ve handled the crisis.

We don’t know where this will go from here. But we still have a chance to seize the crisis as an opportunity to make our economies fairer and rejuvenate our democracies.

I’d like to hear from you! Tell me how you’ve experienced the past week. And, what do you think is the biggest challenge for democracy right now?

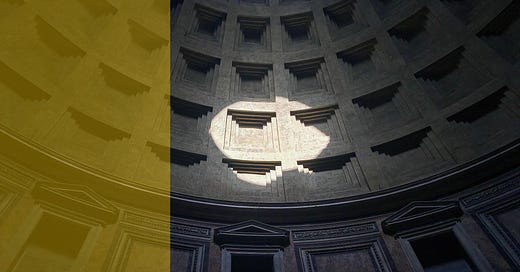

The Pantheon in Rome. Photo by Taylor Smith on Unsplash

It has been quite a week already. That's why, this time, I'll send you my weekly newsletter on a Friday morning instead of on a Sunday.

Thank you for this one. I think it's a threat to democracy that everything has become so opaque... Take the impeachment procedure: I've heard some Republican representatives wanted to vote for impeachment but didn't dare to... what do you make of this? And do you have any recommendations for further reading?